OPERA NEWS

NEW YORK CITY’S enterprising Teatro Grattacielo, dedicated to reviving the works of the verismo/Giovane Scuola era, has been expanding its artistic footprint. Until the Covid lockdown, they presented one concert performance per year. Since the reopening, they have begun staging their offerings, providing satisfying theatrical experiences despite limited means. But Grataciello is giving New York operagoers a taste of unjustly neglected repertoire that stands out from the surfeit of early music, Baroque, and early Classical works that are often the diet of the city’s smaller opera companies. On June 4 under the stars in Battery Park, at the tip of downtown Manhattan, the company unveiled the New York City stage premiere of Riccardo Zandonai’s Giulietta e Romeo.

The work had its premiere at Rome’s Teatro Costanzi in 1922, conducted by the composer and showcasing powerhouse verismo stars Gilda dalla Rizza and Miguel Fleta in the title roles. Though it was not critically beloved, it enjoyed a certain degree of audience success, mostly in Italy and South America. The libretto by Arturo Rossato was inspired not by Shakespeare, but by Italian historical sources. The Capulet and Montague parents are absent, as is Juliet’s nurse, replaced here by her friend and handmaiden Isabella. Romeo and Giulietta’s romance has already begun before the curtain rises; their first scene together, midway through Act I, is a feverish love duet. Although Zandonai’s score is not quite as melodically memorable as his earlier Francesca da Rimini, it certainly displays his talents as a master of orchestral color. Though unmistakably Italian in nature—including the evocative use of some ancient instruments appropriate to the setting—the music has tinges of Debussy, Wagner, and Strauss. It’s all deftly woven by Zandonai into a cohesive and dramatically effective whole. Conducting a reduced orchestra of thirty-one pieces, Christian Capocaccia displayed clear fondness and understanding of Zandonai’s style, and he shone particularly in the opera’s highlight: an orchestral interlude depicting Romeo’s frenzied horseback ride through a storm to Verona when he believes Giulietta has died. (Capocaccia and his cast had to contend all night with a murky amplification system, low-flying helicopters, and chattering audience members, and they did so valiantly.)

As Giulietta, Greek soprano Eleni Calenos sang with a strong sense of phrasing and verismo style, and she acted the role with compelling intensity. There was real chemistry between her and her Romeo, Matthew Vickers, whose beautifully produced lirico-spinto was a pleasure to hear. Both of these roles are strenuous, requiring great stamina and extremes of range; that Calenos sometimes sounded stretched in her uppermost register was not surprising. Tybalt (here Tebaldo) is the villain of the opera; his part is a large one despite his death halfway through, and he spends most of his time condemning and hectoring. Baritone Franco Pomponi is a stagewise veteran who acted the part believably, but he sang with unrelenting force that showed little in the way of dynamic shading and exposed a hard beat in his voice. Tenor Spencer Hamlin made a fine impression in the cameo role of a minstrel, and Melina Jaharis unveiled a lush mezzo as Isabella. Tenor Diego Valdez learned the role of Gregorio on only a few days’ notice and sang it with proficiency. Francesca Federico sang one of the briefest comprimario parts—that of a prostitute—with such strong presence and beauty of tone that she left one longing for more.

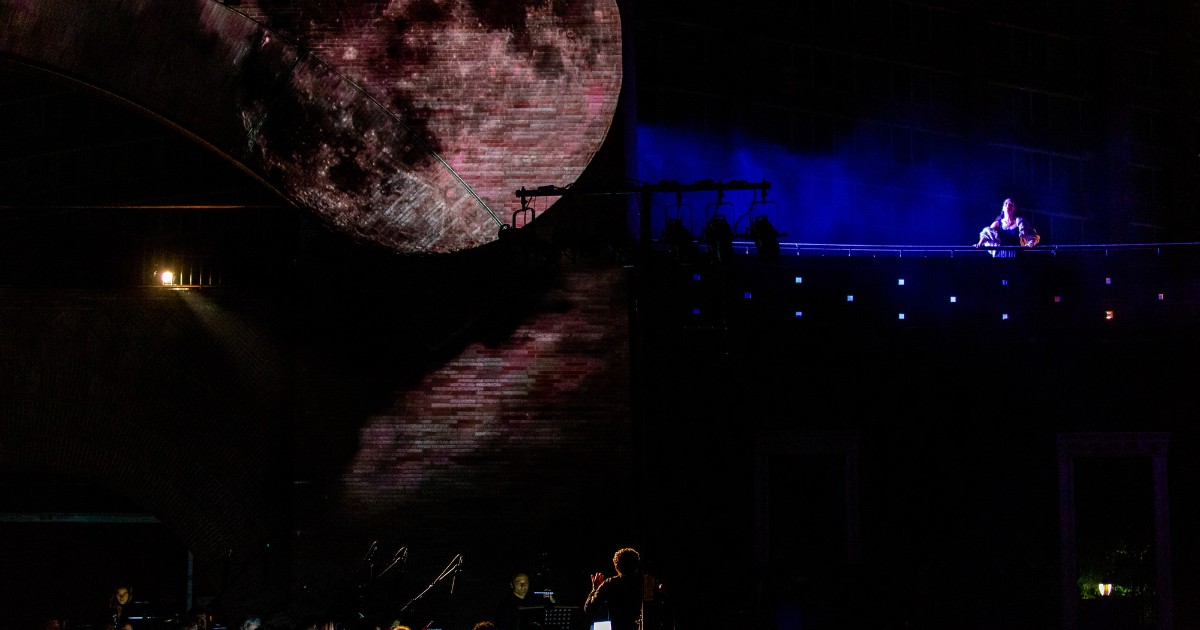

Grattacielo’s general and artistic director Stefanos Koroneos served as director, using the small outdoor stage to maximum effect and drawing committed performances from his cast. His strong stage sense made his decision to use projections designed by Camilla Tassi seem odd; they were superfluous, and at times intrusive. Set and costume designer Tasos Protopsaltou favored black as the color scheme and it worked, producing an effect that was simultaneously stylish and doom-laden, heightened by Lance Lewis’s lighting.

There was a credit in the program for supertitles; somehow, these never materialized, although they would have been helpful to an audience that was experiencing this work for the first time. —

Eric Myers

PARTERRE BOX

The winners of the evening were the composer Riccardo Zandonai and Teatro Grattacielo which pulled off a near-impossible feat with success.

In an intermission interview, the retired soprano Ruth Ann Swenson hypothesized , “What if Gilda really did go to Verona as her father ordered her to, didn’t die and met Romeo instead?” “What ifs” are very tempting (though basically pointless) but Gilda deserves a better man to die for than the Duke of Mantua.

But what about Juliet? I guess she just marries Count Paris like she’s supposed to never knowing any better and becomes an unhappy housewife like her mother Lady Capulet… Is it like the old adage “It is better to have loved and lost than to never have loved at all”? Or maybe it all just sucks—you fall in love, get hurt and then you die.

I sat through two early-Renaissance Italian romantic tragedies this week—Teatro Grattacielo’s Giulietta e Romeo by Riccardo Zandonai and Verdi’s Rigoletto at the Met and I don’t have any answers for you. However, Ruth Ann was right about one thing—cutting loose a lying, two-timing douchebag, making a fresh start and trading up for a younger, fresher and nicer piece is always a good idea.

Stefanos Koroneos, the Greek-born baritone who took over as general and artistic director of Teatro Grattacielo, in the program notes quoted Federica Fortunato, director of the R. Zandonai International Study Center in Rovereto, that “the story of Giulietta e Romeo lends itself to being a metaphor of our time: love, tenderness and friendship opposed to the logic of blood and power.”

But isn’t that most tragic opera including (and especially) Rigoletto where both the jester and his daughter (and their analogues Monterone and his daughter) are sacrificed in blood to the cruel logic of power and privilege?

Zandonai’s opera premiered on February 14, 1922 at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome and is celebrating its centenary this year. There has never been a full production in New York as far as I know. The two performances on June 4 and 5 were the local premiere. The libretto by Arturo Rossato is taken from pre-Shakespearean Italian sources—the novellas of Matteo Bandello and Luigi Da Porto.

Missing in action are Mercutio, the Nurse, Lord and Lady Capulet and crucially Friar Lawrence—also the poetic language of Shakespeare. Rossato’s libretto pits earthy Cavalleria Rusticana type street confrontations against florid poetic allusions in the love scenes excising or minimizing ancillary characters and subplots. What we are left with is a series of intense primal confrontations involving Romeo and Juliet together or Romeo or Juliet versus Tybalt/Tebaldo who embodies the opposition of their families and society.

We start, as in Romeo and Juliet and West Side Story with a confrontation between the Capulets led by Tebaldo (baritone) and the Montagues outside a tavern. The street fighting is stopped by a masked Romeo who counsels an end to violence and hatred. The scene dissolves to the familiar balcony scene encounter between the lovers Romeo and Juliet.

But these lovers have not just met and are not young innocent adolescents—it is clear that they have an ongoing affair and have been physically intimate. Giulietta refers to Romeo as her “husband”. They also don’t sing like teenagers—the score requires a trio of spinto-dramatic soprano/tenor/baritone voices suitable for Tosca or Andrea Chenier.

The second act has a hair-raising confrontation between Tebaldo and Giulietta where he reveals that he knows of her affair with Romeo and demands she marry the Count Lodrone. Romeo makes his way to Giulietta but is intercepted by Tebaldo who challenges him to a duel. Forced to defend himself, Romeo kills Tebaldo and is banished by proclamation of the town herald.

The third act shows Romeo in Mantua (setting of Verdi’s Rigoletto) overhearing a street singer performing a ballad describing the death of Giulietta, the fairest flower of Verona, on her wedding day. Romeo rushes through a storm to the tomb of the Capulets and drinks poison over Giulietta’s supposed corpse. (Cue the opera’s most famous aria “Giulietta, son io” recorded by both the original 1922 Romeo, Miguel Fleta and famously by Mario Del Monaco.

Giulietta awakens, explains about her narcoleptic sleeping draught then dies (ostensibly of a broken heart) with Romeo in ecstatic unison phrases (Shakespeare had Juliet make use of Romeo’s dagger in her final moments).

The dramaturgy is tight and fat-free clocking in under two hours of music. The vocal writing is mostly declamatory with a some extended sections of arioso which do not rise to melodic heights. Giulietta does not have an extended solo aria—a potion scene aria might have made the dramaturgy of the final act somewhat clearer. Zandonai’s musical vocabulary contrasts blood and guts verismo drama against a rather French “art nouveau” impressionistic lyricism evocative of Debussy, Chausson and Fauré.

The somewhat “decadent” impressionistic music also evoked Zandonai’s most famous and successful opera Francesca da Rimini. I found the 2013 Metropolitan Opera Francesca revival difficult to sit through due to the diffuse, empty and sometimes unpleasant score (the miscast leads didn’t help).

A friend once proposed that the stunningly beautiful 1984 physical production by Piero Faggioni with gorgeous sets by Ezio Frigerio and costumes by Franca Squarciapino might be recycled for a superior opera—why not Giulietta e Romeo? All my friends and acquaintances in attendance last Saturday night felt that Giulietta e Romeo was a better opera than Francesca da Rimini. It is shorter, more effective dramatically with a higher level of musical and dramatic intensity and inspiration. (Domingo and Scotto circa 1984 would have done well as the ill-fated Veronese lovers).

Teatro Grattacielo’s production (in collaboration with the Battery Park City Authority) was insanely ambitious and invited mishaps. Though not all was perfection any potential disasters were avoided and the quality of the work shone through. It was presented outdoors on two consecutive nights (not easy on the performers as this is not an ensemble work) in Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park in Battery City Park downtown.

A reduced orchestration for 30 players (down from the 67 in the original score) played live while the singers performed on a postage stamp-sized stage to the right of the orchestra. The brick wall and arches above and behind the orchestra were the backdrop for projections designed by Camilla Tassi—those that were more abstract were more effective.

The set consisted of a black wall with two doorways with a platform or balcony above. The sets and costumes designed by Tasos Protopsaltou tended towards the simple, timeless, functional and all-black. The direction of Stefanos Koroneos was practical, efficient and got the job done with no extras.

Both the solo singers and the orchestra were amplified by what I was told were aerial mikes. I feared the sound cutting out, distortion and even police dispatches being picked up on the mikes. There was none of the above—the sound was clear and well-defined throughout though the miking did add a metallic halo to the singer’s voices.

The orchestra was less well caught by the sound design—it failed to blend with the voices inhabiting a separate parallel sonic landscape. The conducting of the enthusiastic young Italian conductor Christian Capocaccia brought passionate verve to Zandonai’s orchestral composition with clear forward-moving tempos and well-defined textures enhancing the atmospheric drama in the score.

Koroneos’ long experience as a professional singer lends to being a good judge of voices and scouter of vocal talent. The cast was uniformly good and even the smaller roles were cast with accomplished young voices like Jeremy Brauner, David Santiago and Diego Valdez.

As for the leads, tenor Matthew Vickers as Romeo managed the typical verismo high declamatory vocal writing with a rich, plangent tone that was never compromised by forcing or shouting always maintaining a flowing lyric line.

Greek soprano Eleni Calenos did have tonal edge on her forte high notes but was a stylish interpreter with a fascinatingly complex smoky middle register full of resin and shifting dark colors. Calenos is a slender petite woman with a big voice. She has natural stage presence as I witnessed in her Tosca with Loft Opera some years ago in a bus depot in Bushwick. Like other Greek sopranos we could mention, Calenos makes good use of text and dramatic intention.

Baritone Franco Pomponi, many years resident in Europe and popular in France, conquered Tebaldo’s high tessitura and constant testosterone aggression with vocal command and unflagging energy making for a formidable antagonist. Tenor Spencer Hamlin as the Cantatore who imparts heartbreaking news to Romeo in Act III, brought an arresting, bright tenor to the madrigal-like phrases of his ballad. The small chorus was more a collection of solo voices than a blended unit but the voices were fresh and well-rehearsed.

The winners of the evening were the composer Riccardo Zandonai and Teatro Grattacielo which pulled off a near-impossible feat with success.

Eli Jacobson

OPERA, LONDON

New York

Teatro Grattacielo, New York’s specialists in the veristic and post-veristic repertory, are trying new venues and approaches. June 4 brought the first of two outdoor performances (in Battery Park, at the southern tip of Manhattan) of an obscure work in its first local fully professional staging: Zandonai’s Giulietta e Romeo, premiered in Rome in 1922. The score—short of melodic inspiration but full of postWagnerian and post-Debussian atmosphere—has some effective orchestral passages and is strongest in the string writing. As in Francesca da Rimini, his best-known opera, Zandonai employs archaic instruments to convey a sense of the story’s antiquity. Structurally, the forthrightly bodice-ripping libretto bears some similarities to that for Bellini’s Capuleti: we don’t see the lovers meet (they are already pledged in marriage) and many characters employed in Shakespeare’s version are absent—including, strikingly, the entire older generation. Only Tebaldo (Tybalt) speaks for the Capulets. Verona’s laws intrude via a town crier (banditore) who is somewhere between Wagner’s Nightwatchman and Puccini’s Mandarin.

Teatro Grattacielo’s valiant effort had to contend with the usual perils of outdoor urban opera—inopportunely timed helicopters and party boats, crying babies, passing police sirens—as well as the staggering distraction of New York Harbour on a lovely moonlit evening, and amplification that monkeyed with Zandonai’s frequent offstage choral writing. But the dynamic conductor Christian Capocaccia and a committed cast and orchestra put something across, holding the attention of several hundred people despite the challenges. Stefanos Koroneos’s production told the story clearly, with logical blocking in a cramped space that nonetheless allowed for balcony scenes and convincing stage combat. Tasos Protopsaltou’s largely black-and-white costuming succeeded; the company again overdeployed video projections, to little positive effect.

At the opera’s premiere, Zandonai entrusted the roles of the lovers to internationally prominent verismo interpreters: Gilda Dalla Rizza, Puccini’s late-career muse and the creator of Magda in Rondine, and the tempestuous Spanish tenor Miguel Fleta, who two years later would be the first Calaf. Fleta left an impassioned recording of ‘Giulietta, son io’. The roles exert superhuman demands. Despite a few high notes not squarely on pitch, Eleni Calenos (Giulietta) affirmed her affinity for verismo style, impressing with her textual projection and vocal power, singing with a penetrating chest voice and a rich, liquid middle register. As Romeo, Matthew Vickers displayed convincingly Italianate timbre capable of squillo but also a full range of dynamic shadings and remarkable stamina in the high tessitura. Franco Pomponi’s experience as Scarpia and Rance told in his hectoring, full-tilt vocalism as Tebaldo; he commanded the stage. Spencer Hamlin has forged a fine career juggling leading and character tenor roles; he rose to the mournful music of the Ballad Singer who all but hijacks Act 3’s first scene. At short notice, the tenor Diego Valdez learnt and sang Gregorio very creditably. Francesca Federico’s rich soprano and presence had such impact that one wished her part (‘Una donna’—here a spirited sex worker) had been longer.

David Shengold